Deposit outflows swiftly cause a recession in a debt-driven growth model

A further tightening of lending standards will likely lead to negative loan growth

The banking crisis is worsening. And the ongoing deposit outflow is at the root of the problem. The previous episode demonstrated that current policy intervention is likely insufficient to stop the bleeding. And this episode of the Market Routine will give you a concise overview of how declining bank deposits significantly increase the odds of a recession.

Lost deposits

The chart below shows the developments in deposits of US small and large banks. Unsurprisingly, the focus is on the USD 120 billion hit small banks took in the week following the Silicon Valley Bank collapse. That USD 120 billion represents 2.2% of total US small bank deposits leaving in just one week. That same week, large US banks received USD 67 billion in deposits, meaning USD 53 billion in deposits fled the US commercial banking system.

Small banks vs. Large banks

Interestingly, the chart above reveals that large banks had to deal with departing deposits. Large bank deposits have been falling for over a year, whereas small bank deposits have cratered ‘only’ in the last two weeks.

The next chart shows year-on-year deposit growth, which turned negative for large banks in June 2022, while small bank deposits kept growing until October 2022. In addition, despite the USD 120 billion outflow, deposit ‘growth’ is higher for small banks.

Extending the deposit growth chart until 1990 reveals that the current numbers – a 2.1% decline from a year ago for small banks and 2.9% for large banks – are pretty spectacular. US bank deposits seldom shrink on a year-on-year basis, and by more than two percentage points is extremely rare.

Mismanagement

The observations made from the previous charts underpin that it’s not just declining deposits that matter. It also has much to do with what banks do with their deposits. From this perspective, the ‘Silicon Valley Bank is the outlier’ narrative applies, as its unrealized losses were much bigger than those of other regional banks as interest rate hedges were deliberately removed to chase more return. Unfortunately, with banking trust dissolving, the magnitude of potential losses becomes less relevant. And trust is exactly what divides small and large banks these days.

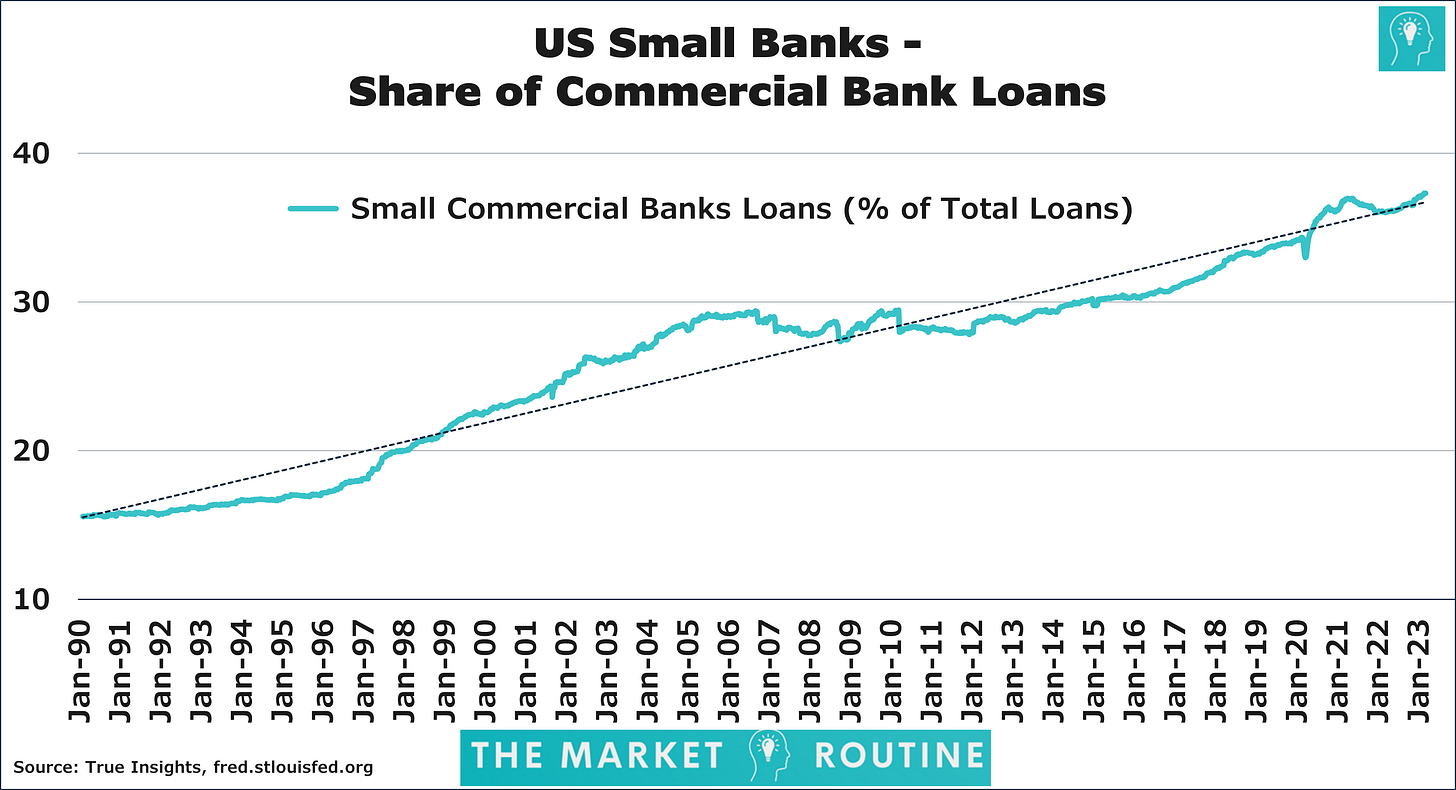

Small bank presence has spiked

The next chart shows the small banks’ share of total commercial bank loans. Since 1990, this share has risen by a whopping 140%, from 15% to over 37%. For Commercial & Industrial loans, it has more than doubled. That’s huge. And confirms that, like Silicon Valley Bank, small banks are by no means ‘small.’

The chart below from BCA shows the loan-to-deposit ratios of small and large US banks. The ratio is significantly higher for small banks. Two implications can be derived from this. First, leverage is higher for small banks, making them more vulnerable to shocks like the massive spike in interest rates we just witnessed. And second, loan growth sensitivity toward declining deposits is higher for small banks. For every USD that leaves a small bank, loan volume is reduced by 0.83 cents, against 0.60 cents for large banks.

Negative loan growth coming

Let’s connect the dots. The Federal Reserve Loan Officer Survey includes 80 domestic US banks, many of which may be classified as a small (regional) bank. The issues at these banks will undoubtedly be reflected in even tighter lending standards. As the chart below reveals, lending standards are already pretty constrained due to the rise in interest rates. Tighter credit conditions were only seen during recessions.

The chart plots the net percentage of survey respondents tightening lending standards forwarded by six months against the year-on-year loan growth of small banks. While this relationship is far from perfect – largely explained by the lagging impact of rising interest rates on the US economy – it’s pretty evident what will happen. Small bank loan growth will dive and likely become negative. This is only seen during some (not all) recessions. This excludes the impact of tighter lending standards on the loan growth of large banks and any potential spillover effects.

Conclusion

Apart from the current policy intervention being too limited to ease the growing concerns over a systemic banking crisis (I wrote about this in my previous post), small banking woes significantly increase the odds of a recession. In hindsight, the additional tightening of lending standards by small US banks due to deposit outflows, unrealized losses, lack of trust, and a depletion of bank capital, may have been the tipping point for the US economy. This is why, contrary to 2022, markets may be right and Powell wrong on interest rates. Unfortunately, one look at earnings expectations reveals that markets are not pricing a recession at this point. I remain cautious about equities and other risky assets like real estate and high yield bonds.