PEPP – Revealing the ECB's Ulterior Motive

With yields spiking, the ECB is buying Italy and selling Germany

Obviously, I'm a big fan of my charts, but now and then, I come across one that deserves credit. And a post! This chart will, once again, underscore the European Central Bank's increasingly explicit target of maintaining debt sustainability.

More equal than others

The chart below, by Robin Brooks, Chief Economist at the Institute of International Finance, shows the net purchases within the ECB's 'pandemic emergency purchase programme' (PEPP), sorted by country.

Since June last year, the ECB has almost exclusively reinvested maturing PEPP bonds in Italian debt. In contrast, the ECB has been a net seller of Dutch and German government bonds. This, of course, is no coincidence.

Capital Keys?

With interest rates rising sharply, it's crucial for the ECB not to let spreads (yield differentials) widen. The 10-year yield on Italian government debt has risen to the highest since 2012, even with relatively benign spread levels. The current Italian yield is higher than in 2010, just before the European debt crisis erupted.

Once upon a time, the ECB bought bonds in line with the capital keys - the share each member state represents in the ECB's capital - which allowed it to disguise that 'debt sustainability' was a (shadow) objective of the central bank. But a lot has changed in recent years, as Brooks' chart shows. And in hindsight, it's fair to say that the ECB embarked on this path of debt sustainability ever since Draghi's famous 'Whatever it takes' speech.

Today, the ECB has left the capital keys far behind.

With the 'Transmission Protection Instrument' (TPI), the ECB has already created a bond-buying black box, where almost no accountability needs to be given for the purchases the bank makes. It's close to 'laughable' when you hear Lagarde say that debt sustainability is not a focal point of the ECB.

The weakest link

The reason bond investors haven't really tested the ECB's willingness to hold things together since 2012 is simple. In exchange for 'good behavior,' these investors received massive amounts of liquidity that allowed them to earn handsome returns.

Therefore, it's interesting to see how far the ECB is willing to go. This is the biggest tightening cycle in the central bank's history, and yet the German 10-year yield remains below 3%. Moreover, the amount of excess liquidity remains still historically high. However, pushing further to regain their credibility as inflation fighters could easily shift the focus to Italy, undoubtedly the 'weakest link' within the half-baked Eurozone. And if there's one thing investors enjoy – and I can confirm - it's testing policymakers.

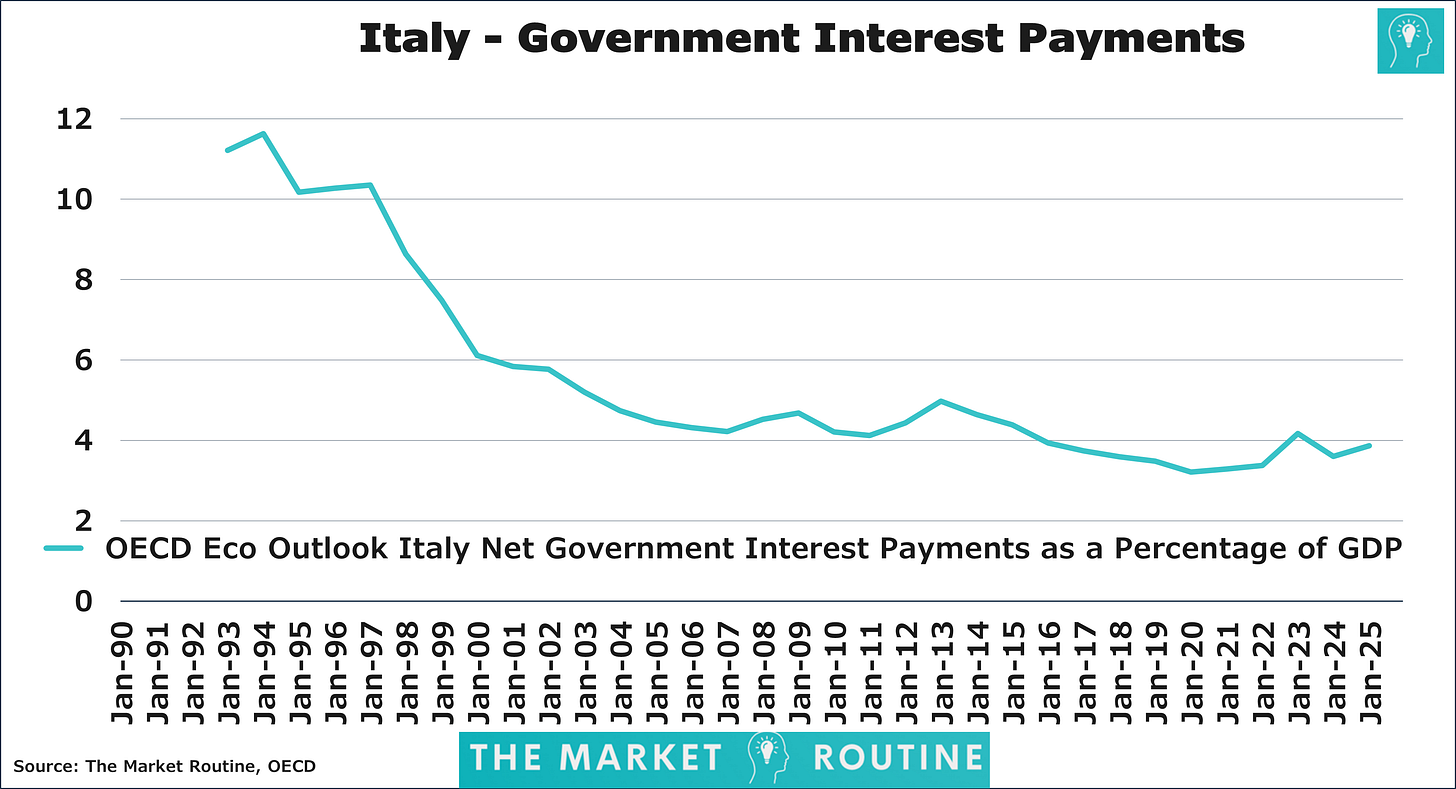

I expect that central banks, and certainly the ECB, won't be able to keep interest rates high for too long. In that case, a new debt crisis will be looming. One reason why this isn't happening now, alongside the ECB's lopsided reinvestment policy, is time. The interest burden as a percentage of GDP is only just beginning to rise. Time will tell!